Kant argues that when the categories are used beyond the boundaries of empirical intuition, claims become “mere forms of thought” that lack objective reality.[1] I start by distinguishing cognizing and thinking; then, to further explain this central distinction, I unpack the basics of judging and clarify their relation to the synthetic unity of apperception. I then partly ground the objective validity of the categories to drive home the distinction so that it is clear why cognizing qualifies as objectively real and why thinking about objects of intuition in general does not. These moves sufficiently explain why the “extension of concepts beyond our sensible intuition does not get us anywhere.”[2]

In the preface, he informs us that “to cognize an object, it is required that I be able to prove its possibility (whether by the testimony of experience from its actuality or a priori through reason). But I can think whatever I like, as long as I do not contradict myself.”[3] When I cognize an object then, there is an empirical intuition associated with such representations that provide the proof such that knowledge follows or in the case of mathematics an a priori justification that depends on the pure forms of intuition. On the other hand, when I think of an object in general there is no direct empirical intuition associated with the representation; it is merely concepts of objects amongst concepts that result in various beliefs. While Kant does not say that beliefs are nonsensical in a derogatory sense, given that he learned to deny knowledge in order to make room for belief;[4] beliefs are technically nonsensical as they are not grounded empirically like cognitions. “Thinking of an object in general through a pure concept of the understanding,” he informs us, “can become cognition only insofar as this concept is related to objects of the senses.”[5]

To further illuminate this distinction and thereby understand his central point in the passage, it helps to clarify his account of judging. For Kant, we are continuously judging because we cannot represent anything to ourselves as unified without judging. The continuous flow of experience is judgment-laden. In general, judgements are ideally composed of two parts, namely intuitions and concepts.[6] These are the “two components [that] belong to cognition,” whereas a thought has only the conceptual component.[7] For our current purposes, it helps to be clear on the basic distinction between analytic and synthetic judgments, both of which presuppose a priori synthesis. The synthetic a priori judgments of the transcendental structure precede conscious judgements because synthetic a priori judgments are what unify objects that are given to the unified self that is aware of what is represented through conscious judgments.

Analytic judgments aim to clarify their initially unified subjects via the “dissolution” of the original synthetic act of the transcendental structure,[8] so they add nothing to their subject terms,[9] whereas synthetic judgments extend the meaning of their subject terms, objects given, through sense.[10] In other words, analytic judgments work to unpack the work of synthetic a priori judgments. Synthesis, he writes, to a unity is opposed to analysis.[11] In contrast, synthetic judgments amplify the “significance” of their subject terms by connecting them with other empirical intuitions and thereby result in the “further extension” of concepts.[12] Connected to all judgments is the ‘I think,’ that is, the various inner representations are always for me, namely for pure apperception.

Pure apperception is the “I think” associated with all of my representations that “stands under every intuition so I can think the object.”[13] Consider the objects you are currently being given in this instant and how, moment-by-moment, those given objects, while changing throughout time, continually remain unified and related to this locus in whatever instant you find yourself thinking in. By being present in any experience pure apperception is the ground of all empirical knowledge. Pure apperception is therefore the true starting point of any account, the “supreme first principle” of all human understanding.[14] Whether I study x, I know y, or I perceive z, I first of all think these different species of judgment. Hence, against pure apperception stand judgments or synthetically unified inner representations. When Kant writes in the passage that some judgment standing against pure apperception lacks intuition, it simply means there is no intuition present for pure apperception to determine the object within the judgment.[15] An instance of such an object would be the universal ideal of “dogness.” Such universals, or objects of intuition in general, for Kant, are not objectively real because universal judgments do not refer to any specific object that appears to the subject, but are forms of thought that apply to many objects for classificatory purposes.

The notion of God, the ideal of pure reason, the universal of universals, illustrates the point. The notion of God lacks objective reality because one cannot point to such an entity “out there” independent of the mind.[16] One route to the notion of God may be having the general first-order concept of a specific sort of rock, or tree, or dog, or any and all other sorts of entities that have objective reality as they appear to someone and when they examine all these different species and attempt to identify their genus, they reflectively construct a larger second-order sort of concept to meet this desire like Universal Being that conjoins all distinct general concepts into a totality. The notion of God, in this instance, as a transcendent idea of reason, is arrived at via synthesizing concepts that are themselves acquired empirically. While this example is a tempting transcendental illusion, such synthetic acts are also errors insofar that these more general concepts, these ens rationis, are taken to exist as things in themselves. To claim such is to use the categories illicitly, i.e., beyond what is ever directly given in experience, so the reflective judgment moves one into indeterminate domains. Further analysis on illicitly acquired things of thought never results in knowledge but only refined belief because there is no specific empirical intuition that such concepts apply to, and so their definitive truth-value must forever remain indeterminate, as he writes, “we cannot even judge whether the latter [objects of intuition in general] are possible or not.”[17] These things of thought have no sense reference but emerge from many inferences. While some may charge Kant with making a ‘category mistake’ by thinking the entēs rationum referents requires a particular intuition like the person who asks to be shown the university in Gilbert Ryle’s popular example, Kant would say those who raise such objections are either applying the categories illicitly beyond experience or deceived by a transcendental illusion and are hypostatizing their constructed notions.

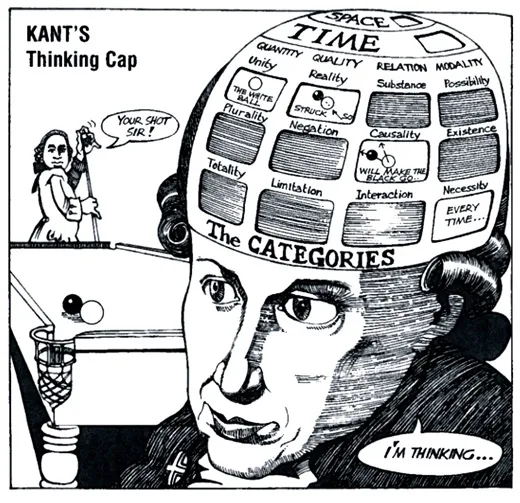

Lastly, the distinction between cognizing and thinking is further elucidated by understanding what is objectively real. To understand what objective reality means in Kant’s system, it is necessary to see the roles of the categories. The categories are the pure concepts of the understanding that Kant claims to discover by examining the grounds of our various forms of judgment.[18] Kant argues, by the transcendental sort of argumentation, that the categories are objectively valid because they are necessary conditions for the possibility of objects to be given in any experience. As he writes, “the objective validity of the categories, as a priori concepts, rests on the fact that through them alone is experience possible.”[19] Kant reckons that if it were not for the categories, experience would not be ordered and unified for me, but would be a complex incoherent array of objects, a “swarm of appearances”[20] for some “multicolored, diverse self.”[21] That experience is clearly not such a swarm motivates Kant to ask how it is that such experience is given at all. In response, he argues that the transcendental structure that comes before experience is responsible. The transcendental structure continuously functions to produce any possible experience via synthetic a priori judgments that process the sensible manifold into a unity. As above, this a priori act precedes any conscious analytic or synthetic judging. The key players in the structure are the categories, which stand under the logical forms of judgement that function to unify our various inner representations. The sensible manifold, however, stands under the categories, and thus the logical forms too, because the categories, through the logical forms, continuously process the manifold to produce a synthesized representation in any possible experience for the synthetic unity of apperception. As proposition twenty in the deduction asserts: “All sensible intuitions stand under the categories, as conditions under which alone their manifold can come together in one consciousness.”[22]

Now, he maintains that “the ground of proof [for the deduction] rests on the represented unity of intuition through which an object is given, which always includes a synthesis of the manifold that is given for an intuition, and already contains the relation of the latter to the unity of apperception.”[23] The quantificational and relational categories help more than others, in my view, to illustrate these abstract claims about the objective validity of the categories concretely because any possible experience contains, prima facie, a plurality of distinct unified substances that appear related in all sorts of ways in space and time. Assuming the veracity of such claims that the categories are in us and functioning within the transcendental structure to produce a unified experience for us, it follows that it is not possible to have an empirical intuition without a concept because the categories, as pure concepts, process the sensible manifold a priori to produce and thereby give any object.

From the categorical determination of the manifold into empirical intuition via the transcendental structure, objective reality follows just as what appears. For Kant, appearance is not an illusion as the traditional appearance-reality distinction maintains; rather, appearance is objective reality because all human subjects process the sensible manifold in the same way in some specific situation as they possess the same transcendental, category-laden structure that produces unified experience. Kant writes, describing his own system of reason, that “the transcendental idealist is an empirical realist, and grants to matter, as appearance, a reality which need not be inferred, but is immediately perceived.”[24] That is to say, what is immediately given, appearance, is what is objectively real. Of course, these objectively real initial cognitions can reach other contingent truths about reality through experience, provided the categories apply to empirical intuition. If one abides by the critical rules, their concepts extend, and they can determine their intuitions in new yet relative ways based on their empirically acquired understanding. As he writes, “in a cognition that thoroughly agrees with the laws of the understanding there is also no error.”[25] However, it is also the case that our initial objectively real cognitions can be misguided and results in “mere forms of thought” when the categories are not applied to empirical intuition but objects of intuition in general.[26] Thus, while he holds that “the category has no other use for the cognition of things than its application to objects of experience,”[27] the categories can, and often are given the nature of human reason, used illicitly when one constructs empty forms of thought from the conditions of the conditioned in their inevitable quest for the unconditioned.[28]

To recapitulate, on the one hand, objective reality then follows cognizing, which is when the categories apply to empirical intuition, on the other hand, objective reality does not follow when the categories are applied free from empirical intuitions, but instead erroneous empty thoughts emerge that may garner various beliefs through thinking, but knowledge cannot follow, our concepts cannot be extended, as cognition is missing the necessary condition of empirical intuition.

[1] Ibid.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., Bxxvi.

[4] Ibid., Bxxx.

[5] Ibid., B146, emphasis mine.

[6] Ibid., B75-6

[7] Ibid. B146.

[8] Ibid., B130.

[9] Ibid., B11.

[10] Ibid., B11.

[11] Ibid., B130.

[12] Ibid., B148

[13] Ibid., B132-34.

[14] Ibid., B136.

[15] Ibid., B148.

[16] In fact, for Kant’s transcendental idealism, no entity has mind-independent existence. All entities exist as mere appearances that are dependent on our categories to be given to us at all, never as independent things in themselves.

[17] Ibid., B148.

[18] Ibid., B95-B107

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid., A111.

[21] Ibid., B134.

[22] Ibid., B143.

[23] Ibid., B144.

[24] Ibid., A371.

[25] Ibid., B350.

[26] Ibid., B148.

[27] Ibid., B146.

[28] Ibid., B394.